Blog Archives

Complex Emotions

Posted by Literary-Titan

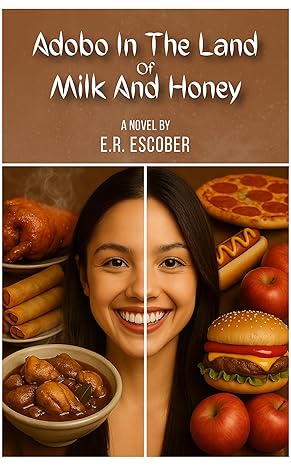

Adobo in the Land of Milk and Honey follows a Filipino-American executive who is sent to the Philippines to oversee the acquisition of a fast-food chain, and instead she finds herself on a deeply personal journey to rediscover her roots and herself. What was the inspiration for the setup of your story?

The emotional authenticity in Mirasol’s journey is unmistakably drawn from my own lived experience.

The Grief That Opens You: Mirasol’s loss of Peter creates the emotional vulnerability that makes transformation possible. I suspect the real grief I’m channeling is the almost four-decade separation from my homeland – that prolonged, unnamed mourning for a cultural self that was never fully developed. Her professional success masking spiritual emptiness reads like my own experience of achieving the American dream while feeling culturally hungry.

The Overwhelming First Tastes: The way I wrote Mirasol’s reaction to authentic Filipino food – that immediate, almost tearful recognition – that’s not imagination. That’s sense memory. That’s me tasting something that awakened parts of myself I thought were gone forever. The specificity of her emotional response to adobo, the way it “loosens something in her chest” – that’s my own homecoming distilled into fiction.

The Shame and Longing: Mirasol’s embarrassment about not speaking Tagalog, her feeling like a fraud in her own culture – this feels deeply personal because it is. The way she simultaneously craves connection and fears exposure as “not Filipino enough” suggests I’ve lived this particular form of cultural impostor syndrome.

The Mother’s Protective Silence: While Jackie’s trauma is fictional, the result – a daughter cut off from her heritage – reflects my own family’s immigration story. The complexity of loving a parent who gave you opportunities by withholding culture feels like a universal immigrant child experience.

The Professional Identity Crisis: Mirasol’s transformation from corporate predator to cultural guardian represents my own late-life reconsideration of what success actually means. After decades of American achievement, finally asking: “But who am I, really?”

The Desperate Need to Save What’s Beautiful: Her fierce protection of Jubilee reads like someone who has finally seen what they’ve been missing and refuses to let it be destroyed. That’s not just character development – that’s the passion of someone who has found their way home and will fight to preserve it for others. I have visited Filipino-inspired restaurants and fast food establishments all over the world and seen the possibility of our Food becoming a worldwide phenomenon. In my own little way, perhaps through this book, I hope to contribute to its popularity and acceptance around the world.

My story becomes a way to process the complex emotions of return – the joy mixed with grief, the recognition mixed with regret, the overwhelming desire to make up for lost time. Mirasol gets to live the homecoming I experienced, but in fiction, I can give her the perfect guide, the transformative mission, the redemptive ending. She carried my heart home.

I found Mirasol to be a very well-written and in-depth character. What was your inspiration for her and her emotional turmoil throughout the story?

Mirasol is indeed a beautifully complex character. My particular struggle inspired her emotional layers, and those of other close friends who went through the same. I hope I was able to “project” these to create such a nuanced protagonist in Marisol.

The Grief-Driven Transformation: Mirasol’s recent loss of Peter creates a vulnerability that makes her open to change in ways she wouldn’t have been before. Her grief seems to strip away her corporate armor, making her more receptive to authentic experiences – like that first taste of adobo that moves her to tears.

Cultural Impostor Syndrome: Her shame about not speaking Tagalog, her awkwardness around Filipino culture, and her simultaneous longing for connection feel drawn from the very real experience of heritage disconnection. She’s Filipino but not Filipino enough, American but carrying something unnameable that America can’t fulfill.

Professional Identity Crisis: The contrast between her corporate success and her emotional emptiness seems inspired by questioning what success really means. When she discovers her company’s true intentions, it forces her to choose between career advancement and personal integrity.

Mother-Daughter Complexity: Her relationship with Jackie – loving but frustrated, seeking connection while being pushed away – adds depth to her character that suggests inspiration from real family dynamics around cultural transmission and generational trauma.

What themes were particularly important for you to explore in this book?

Several profound themes emerge that seem particularly important:

Cultural Inheritance and Interruption: The way trauma can break the chain of cultural transmission feels central to her story. Jackie’s assault didn’t just hurt her – it severed Mirasol’s connection to her heritage. The story captures how historical violence can echo through generations, creating cultural orphans who must fight to reclaim what was stolen.

The Corporate vs. Human Values Conflict: The story is deeply interested in examining how capitalism can be a form of cultural violence. The plan to destroy Jubilee isn’t just business – it’s erasure. The story explores whether it’s possible to succeed professionally while maintaining one’s humanity and cultural integrity.

Food as Cultural DNA: The way I use Filipino cuisine suggests I see food as more than sustenance – it’s memory, identity, resistance. That first taste of adobo, awakening something in Mirasol, feels like I’m exploring how cultural connection can be visceral and immediate, even when intellectual understanding is absent.

The Complexity of “Home”: The exploration of belonging seems particularly nuanced. Home isn’t just geography – it’s culture, family, values, food, language. Mirasol’s journey suggests an interest in how people can create a home rather than just find it.

Collective Action vs. Individual Powerlessness: The way Mirasol builds a community to save Jubilee suggests themes about how meaningful change requires collective effort. Individual good intentions aren’t enough against systemic power.

Redemption Through Cultural Service: Mirasol’s transformation from corporate predator to cultural preservationist feels like you’re exploring whether we can redeem ourselves by serving something larger than our own success.

What is the next book that you are working on, and when can your fans expect it to be out?

Following the publication of “Adobo,” I revisited my debut novel, written 25 years ago, Not My Bowl of Rice. This rereading, a common experience for authors, revealed the melodramatic intensity of my initial work—a whirlwind of passionate romances, bitter rivalries, death, resurrection, shocking betrayals, and unexpected plot twists, culminating in a triumphant resolution, all while richly reflecting the cultural tapestry and values of his homeland. The culinary descriptions, particularly the recipes for Filipino dishes, proved equally captivating, each dish unfolding like a complex narrative with surprising revelations.

This epiphany ignited a transformative vision: Reimagining Not My Bowl of Rice as a telenovela-style semi-graphic novel/cookbook. However, I recognized a deficiency—a lack of visual dynamism, or as Generation Z might say, “optics.” I remedied this by incorporating striking images of characters, locations, and food, resulting in the vibrant rebirth of my debut novel as Not My Bowl of Rice: Telenovela-Style Semi-Graphic Novel and Cookbook! Did I create an entirely new genre of literature? Don’t think so, but I hope the readers will like it- ha-ha!

Author Links: GoodReads | X (Twitter) | Facebook | Amazon

A ghost of her past, Mirasol, estranged from her Tagalog roots, found Manila’s energy igniting a dormant longing. The firm’s actions became a personal betrayal. Adobo, once a symbol of yearning, became a rallying cry.

Torn between heritage and ambition, an unlikely alliance with tour guide Ramon, a man whose contempt for her “Fil-Am” upbringing masked deep resentment, was forged in the crucible of her mother’s dark history. Powerful families, embittered by past grievances against Mirasol’s mother, opposed her. Threats from New York echoed Manila’s suffocating humidity. From Manhattan’s sterile boardrooms to Manila’s vibrant heart, Mirasol faced a visceral reckoning: the agonizing price of belonging, a fierce battle for her soul.

Adobo In the land of Milk and Honey is a cautionary tale of David and Goliath’s scale, except our heroine in Prada heels doesn’t feel like David. She feels like someone who accidentally wandered into the middle of someone else’s battle and somehow ended up holding a slingshot. What would be her next move? The city held its breath, waiting. The scent of adobo hung heavy, a promise of either redemption or ruin.

Share this:

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window) Tumblr

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window) Pocket

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window) Telegram

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window) WhatsApp

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

Posted in Interviews

Tags: Adobo In The Land Of Milk And Honey, author, book, book recommendations, book review, Book Reviews, book shelf, bookblogger, books, books to read, culture, E.R. Escober, ebook, fiction, Filipino-American culture, goodreads, indie author, kindle, kobo, literature, Literature & Fiction, nook, novel, read, reader, reading, story, writer, writing

Adobo In The Land Of Milk and Honey

Posted by Literary Titan

E.R. Escober’s Adobo in the Land of Milk and Honey is, at its heart, a story about identity, loss, and the complicated dance between assimilation and heritage. We follow Mirasol Mendoza Moreau, a sharp and ambitious Filipino-American executive who is sent to the Philippines to oversee the acquisition of a struggling fast-food chain, Pinoy Jubilee. What begins as a business assignment quickly becomes a deeply personal journey, forcing her to reckon with her late boyfriend’s absence, her mother’s silence about the homeland, and the messy, beautiful reality of a culture she has always kept at arm’s length.

Escober’s prose is remarkably vivid; rather than merely describing Manila, he immerses the reader in it. The airport scene, in which Mirasol is immediately enveloped by a wall of heat and commotion, vendors calling out, families embracing in noisy reunions, captures the overwhelming disorientation of arrival with striking immediacy. And later, the kalesa ride through Intramuros, Mirasol annoyed, Ramon smug, the horse nosing her shoulder, was both funny and strangely tender. I loved how Escober uses small, almost absurd details (like a horse drooling on a silk blouse) to pull Mirasol out of her polished New York shell. The writing has this knack for being sharp one moment and unexpectedly warm the next, which felt very true to the push and pull of identity crises.

What stood out most to me was how food served as the narrative’s foundation. The balut scene is a perfect example: Mirasol, determined to prove she isn’t just another “Fil-Am tourist,” dives into the duck embryo with salt and chili while Ramon watches like a judge at a reality show. It could have been written for laughs, but instead, it becomes a turning point, breaking down Ramon’s skepticism and showing Mirasol’s willingness to embrace discomfort. Later, when she eats Rosa’s adobo at the original Pinoy Jubilee, it isn’t just a meal, it’s an initiation into the heart of what the restaurant represents: family recipes, sacrifice, and tradition. Escober makes food not just symbolic, but alive, messy, and deeply emotional.

I felt conflicted about Ramon; his air of superiority often proved as frustrating for me as it was for Mirasol. His constant testing, comparing her to Olivia Rodrigo, making her ride a kalesa instead of a car, lecturing her about “real” Filipino culture, sometimes felt heavy-handed. But then Escober complicates him by revealing his own past heartbreak with another Fil-Am who “came back home” only to leave again. Suddenly, his sharp edges made sense. He wasn’t just gatekeeping culture; he was guarding against disappointment. That shift made him more compelling, and I found myself grudgingly rooting for the dynamic between him and Mirasol to thaw.

By the time I closed the book, I felt like I had been on the journey with Mirasol, not just through Manila’s crowded streets, but through the strange space of being between two worlds. Escober doesn’t sugarcoat it. The book is messy, emotional, and sometimes frustrating, but that’s exactly why it works. It’s not a polished postcard of the Philippines; it’s a story about finding pieces of yourself in unexpected places, whether in a noisy street market or in a bowl of perfectly braised adobo.

I’d recommend Adobo in the Land of Milk and Honey to anyone who enjoys stories about identity, grief, and rediscovery, especially second-generation immigrants who’ve ever felt the pull of a “homeland” that doesn’t quite feel like home. Even if you’ve never wrestled with cultural roots, the humor, the romance, and the sheer sensory detail make this a rich, rewarding read. It’s not just a business story. It’s not just a food story. It’s a story about being human and hungry, for meaning, for connection, and, for really good adobo.

Pages: 302 | ASIN : B0FHSZ95N7

Share this:

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window) Tumblr

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window) Pocket

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window) Telegram

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window) WhatsApp

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

Posted in Book Reviews, Five Stars

Tags: Adobo In The Land Of Milk And Honey, author, book, book recommendations, book review, Book Reviews, book shelf, bookblogger, books, books to read, contemporary, E.R. Escober, ebook, fiction, goodreads, immigration, indie author, kindle, kobo, literature, nook, novel, read, reader, reading, story, writer, writing