Blog Archives

Human History is Brutal

Posted by Literary Titan

Montjoy: A Novel in Five Verges follows a Jewish professor and historian grappling with personal and professional crises who is entrusted with a Nazi diary written by a camp guard. What was the inspiration for the setup of your story?

Montjoy unfolded over many years and many iterations. I originally envisioned the story as a classic revenge narrative, but felt it trivialized events, and pointed to the same myths that Walter Benjamin criticized. Benjamin was an enormous inspiration for this book (Montjoy would not exist without the Frankfurt School of philosophers), and the story is very much told from an anti-historicist perspective. Like my protagonist Owen Schoenberg, I had to understand that history cannot be understood as a linear version of events. History is a shadowplay between past and present, and never truly done with us. This is most exemplified by the Ungeist character, who is like a ghost that can’t be chased away. Human history is brutal, unforgiving and ugly, but it is who we are. Once I realized this, there was no way I could go back to my original story. It seemed superfluous by then.

What were some goals you set for yourself as a writer in this book?

I don’t start out with a set of goals necessarily, but I did know that I wanted to experiment with the historical fiction narrative, and create something that felt close to a documentary. Writers like W.G. Sebald, Thomas Bernhard, Paul Auster and J.G. Ballard (his book Running Wild especially) were huge inspirations to me while writing Montjoy, and I wanted to play with fiction and non-fiction elements almost like a Hegelian dialectic. However, what I arrived at was Theodor Adorno’s notion of the negative dialectic, where contradictions are upheld and no easy resolution is possible. This is what Owen Schoenberg eventually has to grapple with. Behind the more philosophical elements of the story, I wanted to write a story about loss, and how someone who is emotionally closed off deals with that. Owen Schoenberg looks at everything through a non-fiction lens, so it was only natural that he would be consumed by fictions. The merkbuch as well as a version of his son that never existed.

What were some themes that were important for you to explore in this book?

Response: Obviously, the war on truth is concerning for us all and I wanted to show how important it is that we stick to the facts. Wittgenstein said that “the world is the totality of facts, not of things” and I would be hard pressed to see his logic anywhere in the world today. Montjoy explores many subjects (anti-historicism, the Holocaust, the Nazi war machine and its bureaucracy), but most crucial is the embrace of facts, which are not always easy to confirm and can be hijacked by conspiracies. As we are well aware, the truth is now easier to manipulate, skewer and propagandize, and I wanted to show the dangers of such myths and where they can lead. Orwell feared that objective truth was fading out of the world and lies would be our history. Montjoy makes a case for the truth and all its illusions.

What is the next book that you are working on, and when can your fans expect it to be out?

My next book is another historical mystery that shares some of the same themes as Montjoy, but from a completely different angle. I am currently in the writing stage with an eye on a 2026 release.

Author Links: GoodReads | X | Facebook | Instagram

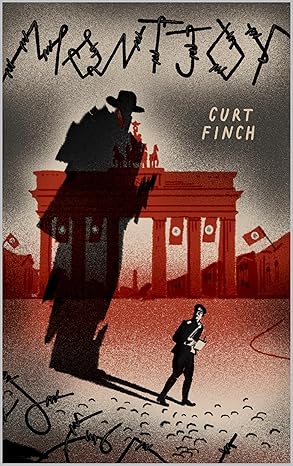

Told in an experimental style that echoes the works of W.G. Sebald and Iain Sinclair, Montjoy is a chilling story about the ghosts of history and the shadows that linger long after the clock tolls.

Share this:

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window) Tumblr

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window) Pocket

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window) Telegram

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window) WhatsApp

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

Posted in Interviews

Tags: author, book, book recommendations, book review, Book Reviews, book shelf, bookblogger, books, books to read, Curt Finch, ebook, fiction, goodreads, historical fiction, indie author, kindle, kobo, literature, Montjoy, nook, novel, read, reader, reading, story, writer, writing

Montjoy

Posted by Literary Titan

Curt Finch’s Montjoy is a narrative shaped by loss, memory, and the weight of history. Told through the reflective lens of its protagonist, Owen Schoenberg, a historian grappling with personal and professional crises, the novel traverses Europe, exploring Manchester, Vienna, Berlin, Linz, and finally a return home. Finch weaves together themes of grief, identity, and the search for meaning against the backdrop of Holocaust history and contemporary existential malaise.

One of the most striking aspects of the book is Finch’s writing style. It’s intricate, even meandering at times, with sentences that seem to mirror the protagonist’s restless and pensive state of mind. There’s an early scene in Manchester where Owen receives a phone call from Ella Grunebaum that sets the story in motion. Finch writes with a blend of dry humor and melancholy that hooked me immediately. Owen’s ruminations—on the collapse of his marriage, the death of his son, and his Baillie Gifford Prize for a book that feels hollow in hindsight—strike a deeply human chord. Finch captures the emotional weight of these experiences without tipping into melodrama. The balance between Owen’s sharp wit and his palpable sorrow made him a compelling, if occasionally infuriating, narrator.

Vienna—the second “verge”—is where the novel truly shines. Here, Owen immerses himself in the archives of the Mauthausen Memorial, unearthing both historical and personal truths. The city becomes a character in itself, with its wintry streets and grand cafés reflecting Owen’s internal isolation. Finch excels in painting Vienna as a place of contradictions: cultured yet haunted, vibrant yet subdued. A particularly vivid moment is a dinner with Ella and her husband Noah, where the conversation spirals into philosophical debates about memory, history, and the ethics of storytelling. This scene epitomizes the book’s intellectual richness, though at times, the dialogue can feel academic. Still, it’s these dense exchanges that give the narrative its weight and texture.

One aspect I found challenging was the novel’s pacing, especially in Berlin and Linz. While Finch’s prose remains evocative, the plot occasionally feels bogged down by Owen’s introspection and the historical detail. For instance, Owen’s discovery of the mysterious “merkbuch” in Linz—a journal buried at the Mauthausen site—is a fascinating thread, yet its unraveling is slow and laden with tangents. That said, the merkbuch’s contents—recounting acts of defiance and despair during the Nazi era—are haunting and memorable, raising questions about the interplay of fact and fiction, morality and survival.

By the time Owen returns “home” in the final verge, the novel feels like it’s circling back on itself, much like its protagonist. The ending is understated yet poignant, leaving more questions than answers. I found it fitting for a story so concerned with the elusive nature of truth and reconciliation. Finch doesn’t offer easy resolutions, and that’s precisely what makes the book linger in your mind.

Montjoy is a novel for readers who enjoy thought-provoking literature steeped in history and philosophy. Fans of W.G. Sebald or John Banville will likely find much to admire here. For me, it was a moving and intellectually rewarding read, though one that demanded patience and reflection. Finch has crafted a novel that’s as much about the stories we tell ourselves as it is about the ones we uncover in the world around us.

Pages: 147 | ASIN : B0DLLHSTY7

Share this:

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window) Tumblr

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window) Pocket

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window) Telegram

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window) WhatsApp

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

Posted in Book Reviews, Four Stars

Tags: author, book, book recommendations, book review, Book Reviews, book shelf, bookblogger, books, books to read, Curt Finch, ebook, fiction, goodreads, historical fiction, indie author, kindle, kobo, literary fiction, literature, Montjoy, nook, novel, read, reader, reading, story, war fiction, writer, writing, WWII Fiction