Blog Archives

Sifting Through Memories

Posted by Literary-Titan

A Pleasant Fiction follows a middle-aged man as he prepares his parents’ home for sale after their deaths, navigating the rooms of his childhood one last time and unearthing long-buried memories. What was the inspiration for the setup of your story?

The setup came from a very real place. After my own father passed away last year, I found myself in the exact position Calvin is in—sorting through the physical and emotional remnants of a life once shared. It’s a process that’s equal parts grief, memory, and reckoning. The house in A Pleasant Fiction becomes a kind of emotional topography. Each room holds its own ghosts, each item its own story, and the act of cleaning it out becomes a meditation on meaning, family, and what we carry forward.

One of the hardest parts was letting go of the things—not just because they had sentimental value, but because they felt like all that was left. Giving or throwing them away felt like saying goodbye again, and maybe for the last time. But eventually, out of necessity if nothing else, you realize you can’t keep 80 years of someone else’s life in boxes. And when you accept that, something shifts. You begin to understand that what remains isn’t the stuff—just as the people you loved weren’t only their physical bodies—it’s the memories attached to them and the impact they had on you. You can let go of the things without letting go of the person. The love, the lessons, the echoes—that’s what endures. So the house and the process of letting go becomes a metaphor for that deeper truth. It’s not about holding on to what was, but learning to carry forward what still matters.

It seemed like you took your time in building the characters and the story to great emotional effect. How did you manage the pacing of the story while keeping readers engaged?

The pacing was deliberate—almost musical. I wasn’t writing toward a traditional climax so much as riding waves of emotion, like experiencing the movements of a symphony. There are motifs that return, refrains that echo. The structure is non-linear because grief isn’t linear. It loops, it lingers, it ambushes you. You think you’ve moved past one feeling, and then it washes over you again in a different key.

And while the book is ultimately structured around the five stages of grief, I didn’t outline it that way ahead of time. If I had started with that framework, I think it would have felt artificial—too linear and orderly for something as inherently chaotic as real grief. Instead, I focused on the emotions I went through while settling my own parents’ estates and let the story tell itself. And in that process, the five stages revealed themselves organically—in all their messiness and overlap.

There’s also a kind of chain reaction that happens when you’re sifting through memories like this. One object sparks a memory, which sets off another, and then another. It’s not just nostalgia—it’s more like activating a neural network. Each association sparks the next, building its own momentum, and you find yourself pulled deeper and deeper into a sequence of emotional discoveries. That dynamic shaped the book’s rhythm. It’s why the story doesn’t move in a straight line but follows the emotional logic of memory itself.

What keeps readers engaged, I think, is that Calvin isn’t just telling a story—he’s actively processing it, in real-time, with the reader. There’s vulnerability in that. And maybe, if it’s working, there’s catharsis too.

I find that, while writing, you sometimes ask questions and have the characters answer them. Do you find that to be true? What questions did you ask yourself while writing this story?

Absolutely. Writing for me is a form of philosophical inquiry. I’m less interested in delivering answers and more concerned with framing the right questions—questions that keep echoing long after the book ends.

In A Pleasant Fiction, one of the core questions Calvin keeps circling back to is: Did they know how much I loved them? It’s heartbreaking because in some cases the answer is clearly no—and not just among the dead. That realization carries its own kind of grief, but also a kind of salvation. Because for the people still here, you still have a chance. You can say the thing. You can show the love.

There are theological questions too—ones Calvin doesn’t always like the answers to: Is this really the best an omnipotent and omnibenevolent being can do? What is the point of all this suffering? But also more human-scale ones: Are we better off when we don’t get the thing we want? And if so, were we wrong to want it? What is the cost of noble self-sacrifice to those who rely on your presence? Is the best we can do ever really enough when facing a no-win situation?

There’s also a quieter question that haunts the edges of the narrative: Who am I to grieve for someone I barely knew? That might mean a Facebook friend—someone whose life ended up touching yours in ways it never did when you were physically in the same place. There’s an irony in feeling closer to someone through written posts and late-night messages than you ever did sitting across from them in a classroom. But it’s not about the medium—it’s about the substance of the interaction. You can sit in front of someone and still not see them. And sometimes, through the filter of distance or time or reflection, something more real emerges.

Or it might mean an unborn child—someone you never met, but whose absence still lingers. Grief doesn’t always follow logic. Sometimes it reveals what mattered to us more than we understood in the moment.

Some of these questions Calvin voices directly. Others are embedded in his contradictions—how he says one thing but shows another. That tension is intentional. Even when we think we’re being honest, we’re still performing a version of ourselves. Calvin often presents possible answers, but the reader doesn’t have to agree with them. They’re not conclusions—they’re invitations. Sometimes Calvin’s answer is literally, “I don’t know.” The book isn’t trying to resolve these questions so much as asking the reader to sit with them, to feel them, and maybe to bring their own answers to the table.

What is the next book that you are working on, and when can your fans expect it to be out?

Right now, I’m putting the finishing touches on Coming of Age, Coming to Terms, a companion volume for readers who want to dig deeper into the themes, characters, and questions raised in The Wake of Expectations and A Pleasant Fiction. It’s over 300 pages and really exposes the underlying emotional architecture of the series. It will be available as a free ebook for readers who join the email list and should be released around the same time A Pleasant Fiction comes out—early July.

I’m also releasing a serialized version of The Wake of Expectations—starting with Becoming Calvin—as a more accessible entry point for new readers who might be intimidated by the full novel. And I’m planning to release the first audiobook this fall, most likely beginning with Becoming Calvin as well.

As for what’s next, I’m working on a new novel, tentatively titled Last Summer. It’s still in the early stages, but tonally, you might think of it as The Sopranos meets The Goonies—a 1980s coming-of-age story featuring some familiar faces. It’s sort of a YA novel with dark humor. I’m aiming for a 2026 release.

Author Links: Goodreads | X (Twitter) | Facebook | Website | Amazon

Calvin McShane has lost everyone who made him who he is. As he prepares his parents’ home for sale after their deaths, he navigates the rooms of his childhood one last time—sorting through his family’s belongings, unearthing long-buried memories, and reckoning with the weight of what was said, what was left unsaid, and what was never truly heard.

Set in the quiet spaces between loss and remembrance, A Pleasant Fiction is an immersive and unflinchingly honest novelistic memoir, blending lived experience with literary storytelling. With raw vulnerability and emotional depth, Calvin revisits his past—his complicated family, his long-abandoned musical ambitions, and the friendships that shaped him—searching for meaning in what remains.

A deeply personal and profoundly emotional meditation on grief, love, loss, and identity, A Pleasant Fiction explores the bittersweet reality of memory and the struggle to move forward without leaving the past behind.

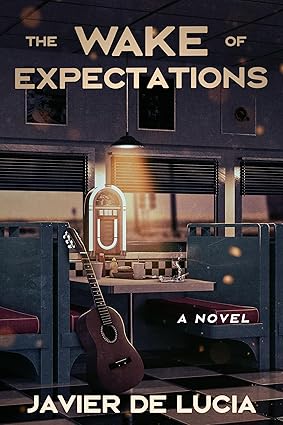

The follow-up to De Lucia’s debut novel, The Wake of Expectations, A Pleasant Fiction revisits its central characters a quarter-century later, revealing how time, loss, and perspective can reshape even our most intimate truths.

Share this:

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window) Tumblr

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window) Pocket

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window) Telegram

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window) WhatsApp

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

Posted in Interviews

Tags: A Pleasant Fiction, author, book, book recommendations, book review, Book Reviews, book shelf, bookblogger, books, books to read, coping, ebook, family, fiction, goodreads, grief, indie author, Javier De Lucia, kindle, kobo, literature, nook, novel, read, reader, reading, realistic fiction, series, story, theological, writer, writing

A Pleasant Fiction: A Novelistic Memoir

Posted by Literary Titan

In A Pleasant Fiction, Javier De Lucia delivers the emotionally resonant second act to his two-part coming-of-age story, continuing the story of Calvin McShane where The Wake of Expectations left off. If the first book chronicles adolescence in all its messy, comic glory—equal parts coming-of-age tale and Gen X time capsule—A Pleasant Fiction is its older, wiser, and more painful counterpart. Together, the two novels form a sweeping narrative arc that spans the giddy freedom of youth through the disillusionment and hard-earned wisdom of middle age.

De Lucia’s central theme in A Pleasant Fiction is grief, but not grief as an isolated event. This is grief as a condition of life, one that shapes identity and outlook. The book becomes a study in how people carry grief, how they adapt to it, and what they do with the space it leaves behind. But grief here is never cheapened into sentimentality. Calvin’s decisions are morally murky, especially as they pertain to his disabled brother Jared. That’s what makes De Lucia’s work so affecting: the absence of clear heroes or villains. Just people, burdened with love and trying not to collapse under it.

Jared is more than a side character; he is the axis around which the McShane family orbits. His needs shape their routines, his presence defines their household, and his vulnerability tests the limits of their resilience. De Lucia treats Jared not as a symbol, but as a person. For Calvin, Jared represents both the weight of responsibility and the purity of unconditional love. Their relationship is rendered with tenderness and brutal honesty. In one unforgettable line, Calvin reflects: “Loving him was hard. Not loving him was even harder.” That one sentence captures the emotional complexity of being a sibling to someone whose suffering is constant and visible. Jared’s life, and ultimately his death, transform Calvin’s understanding of love, sacrifice, and meaning.

A Pleasant Fiction elevates the series from charming autobiographical fiction to something far more profound. In its patient, unsparing look at illness, family, and the work of grief, the novel finds meaning not in plot twists or dramatic revelations, but in the simple, difficult act of enduring. As Calvin muses in the closing pages, maybe the idea of reunion, of eternal peace, is just “a pleasant fiction.” This is a novel about what it means to grow up and grow older. And for those who have loved and lost, it rings painfully and beautifully true.

Pages: 203 | ASIN : B0F4L1R9K5

Share this:

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window) Tumblr

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window) Pocket

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window) Telegram

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window) WhatsApp

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

Posted in Book Reviews, Five Stars

Tags: A Pleasant Fiction: A Novelistic Memoir, author, biographical fiction, book, book recommendations, book review, Book Reviews, book shelf, bookblogger, books, books to read, ebook, fiction, goodreads, indie author, Javier De Lucia, kindle, kobo, literary fiction, literature, memoir, nook, novel, read, reader, reading, story, writer, writing

Isolation vs. Connection

Posted by Literary-Titan

The Wake of Expectations is a raw, poetic unraveling of self in a world where dreams, disillusionment, and the pressure to perform collide. What was the inspiration for the setup of your story?

I’m totally Gen X and that rawness of self-expression—that disillusionment, too—that’s a function of my generation, a by-product of our obsession with authenticity. We were probably the first generation told we could be anything we wanted to be, but we were largely left to figure things out on our own. That contradiction creates an inevitable gap between expectation and reality.

On a more personal level, I’m a huge Kevin Smith fan. I remember him talking about not seeing his friends or his world represented on film, so he decided to make it himself. And that was mostly the impetus for writing this book: a desire to see our version of reality represented somewhere—to create something of artistic permanence to stake our claim that we were here, too. Honestly, I would rather have made a movie or a TV series, but writing a book was just more practical.

Are there any emotions or memories from your own life that you put into your character’s life?

Pretty much everything in my main character’s life is rooted in emotions or memories from my own. The story is fiction, but it’s emotionally true. Like Calvin, I wanted to be a musician. I had a girlfriend who dumped me when she went away to college. I had differences with my parents. But more than anything, I wanted to capture the longing, the frustration, the impatience—the alienation in that process of becoming. That feeling of champing at the bit, staring at a world of possibility, but being unable to get out of the starting blocks. It’s personal, but it’s also generational. Ironically, I never really felt part of my cohort, but that’s exactly what made me representative of it. I tried to capture that paradox in the book.

What were some themes that were important for you to explore in this book?

I wanted to ask questions more than present answers: What do you do when your dreams come true but don’t live up to the hype? Is it wrong to want something you can’t have? Is it sometimes better not to get what you want? And how do you become the person you’re meant to be when you don’t even know who that is yet?

A recurring theme is the desire to be fully seen—but never quite achieving it, even among people who clearly love you. That’s a major part of Calvin’s disillusionment. At his core, he’s searching for connection on his terms, not anyone else’s—and that proves elusive. He’s caught in this constant push-pull: authenticity with isolation vs. connection with compromise. And again, I think that tension is a very Gen X dilemma.

What is the next book that you are working on, and when can your fans expect it to be out?

The next book is A Pleasant Fiction: A Novelistic Memoir, and it releases on July 1—just a month after Wake (June 3). It follows the same group of characters 25 years later, and the proximity in release dates is no accident. A Pleasant Fiction is a follow-up, but not exactly a sequel. It’s a very different book—slower, more meditative—and it reframes everything in the first book. Wake is a complete work on its own, but A Pleasant Fiction is essential reading if you want to fully understand it.

I actually wrote the first draft of Wake over 20 years ago. So that book carries the reflections of a 30-year-old looking back on his twenties. The next one captures a 50-year-old grappling with the challenges of middle age. Together, they form a diptych—a two-panel meditation on the passage of time, told authentically from opposite ends of the timeline. It’s more of a dialogue than a sequence, tracing the coming-of-age through the unbecoming of middle age.

Author Links: GoodReads | X (Twitter) | Facebook | Website | Amazon

He’s just been accepted into his dream college, and his parents have won the lottery. But instead of celebrating, he finds himself drifting further from the people he loves and the future he imagined.

Set in a time before smartphones, when connection meant looking across the table instead of into a screen, The Wake of Expectations is a funny, heartfelt, and deeply human exploration of dreams deferred and dreams derailed, the courage to choose your own path, and the transformative power of love, friendship and self-discovery.

A raunchy, Gen X coming-of-age story brimming with 1990s nostalgia, The Wake of Expectations follows Calvin on an unflinching, deeply immersive journey that blends edgy humor with serious introspection, offering a biting look at the messiness of growing up. Through Calvin’s sharp, often self-deprecating lens, the novel presents a cast of richly drawn, complex characters and relationships worthy of deep literary analysis.

Mature themes and adult humor are woven throughout, so reader discretion is advised.

Share this:

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window) Tumblr

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window) Pocket

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window) Telegram

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window) WhatsApp

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

Posted in Interviews

Tags: Asian American & Pacific Islander Literature, author, biographical fiction, Biographical Literary Fiction, book, book recommendations, book review, Book Reviews, book shelf, bookblogger, books, books to read, ebook, fiction, Gen X, goodreads, indie author, Javier De Lucia, kindle, kobo, literature, nook, novel, read, reader, reading, story, The Wake of Expectations, writer, writing

The Wake of Expectations

Posted by Literary Titan

Javier De Lucia’s The Wake of Expectations is a raw, poetic unraveling of self in a world where dreams, disillusionment, and the pressure to perform collide. The book journeys through a fragmented psyche, moving between poetic introspection and philosophical musings, all while probing the cost of living under the weight of inherited ideals and cultural norms. It’s less a narrative and more a lyrical excavation—a fevered diary torn at the seams.

What struck me first was the voice. It’s angry, tender, lost, and deeply human. De Lucia doesn’t hold your hand. He throws you in. His words crackle with emotion—grief, rage, shame. The prose can be jagged, like broken glass, but that’s the point. It’s meant to cut. It’s meant to hurt. And it does, in the best way. I found myself underlining lines not because they were pretty, but because they felt true. Like he’d scooped thoughts out of the back of my mind and dared to say them out loud.

But some passages drift into abstraction. There were moments when it felt like De Lucia was writing for himself. It’s unapologetically personal, but it’s fantastic when it lands; however, I craved more shape and clarity. Still, even in its chaos, there’s something magnetic about it.

The ideas in the book were thought-provoking, and something I really enjoyed about this novel. He questions everything: ambition, masculinity, belonging, even time. And he doesn’t offer answers. Just cracks. Openings. Invitations to think, to feel. I came away shaken, but also strangely comforted. There’s something healing in the honesty, in knowing someone else is just as bewildered by the world.

The Wake of Expectations isn’t for everyone. It’s heavy. It’s weird. It doesn’t pretend to be neat or nice. But if you’ve ever felt like you’re drowning in who you’re supposed to be, this book might throw you a rope—or at least show you you’re not alone. I’d recommend it to readers who crave emotion over plot, who aren’t afraid of the dark corners. It’s poetry with teeth. And it lingers.

Pages: 551 | ASIN : B0DYBJVG9C

Share this:

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window) Tumblr

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window) Pocket

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window) Telegram

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window) WhatsApp

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

Posted in Book Reviews, Four Stars

Tags: author, biographical fiction, book, book recommendations, book review, Book Reviews, book shelf, bookblogger, books, books to read, coming of age, ebook, goodreads, humorous, indie author, Javier De Lucia, kindle, kobo, literature, nook, novel, read, reader, reading, story, The Wake of Expectations, writer, writing